Hege Storhaug, HRS

Når talspersoner som Abid Raja, Akhtar Chaudhry, Athar Ali, Khalid Mahmoud med flere, anklager Norge generelt og norske enkeltpersoner spesielt for rasisme, burde man sette foten kontant ned i protest. Selvsagt kjenner disse personene meget godt til rasismen i Pakistan, og undertrykkelsen i kastesystemet. Selvsagt kjenner de meget godt til at disse avskyelige holdningene er importert hit. I tillegg kjenner de vel så godt til synet på ikke-muslimer i egne rekker. Likevel har de turet frem i alle år med rasismekortet, slik eksempelvis Raja gjør det her under sitt personlige show på Litteraturhuset (gå til ca 7 minutter i videoen). Det er så uredelig som det kan bli. Fullstendig usmakelig. Men du verden så godt rasismekortet har fungert. Det lammer den kritiske fornuften, det hemmer reell problematikk å komme på bordet, og det raserer muligheten for å rydde opp i den mest omfattende rasismen vi har i Norge, den som trives så godt i ikke-vestlige miljø.

Hvem husker ikke også hvordan Raja spilte rasismekortet i egen storfamilie, da han truet med å gifte seg med en norsk jente hvis han ikke fikk ekte norskpakistanske Nadia? En mer avslørende historie fortalt av ham selv skal man lete lenge etter.

Disse talspersonene har notorisk utnyttet veikheten til politikerne og journalister, og de samme sin mangel på kunnskap om faktiske forhold. Kanskje på tide at Raja og co begynner å koste utenfor den riktige døren, sånn ca 40 år etter at pakistanere begynte å innvandre til Norge og nå som 3.generasjon vokser opp med samme holdninger som besteforeldrene?

|

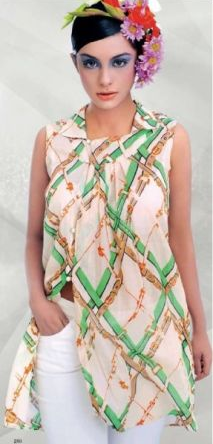

Rooshanie som modell i Pakistan. Legg merke til at hun sminkes til langt lysere i huden enn hun er. |

A racist’s perspective

By Rooshanie Ejaz, HRS

(Islamabad) In recent European debates, one can detect palpable tension when the issue of racism comes up. The topic arises in connection with a wide spectrum of phenomena: it’s one thing, after all, to deny young people of Asian origin entry into a hip nightclub in Copenhagen, and it’s entirely another to murder one’s daughter because she married a Kashmiri Muslim instead of a Punjabi Muslim. My opinion is that it’s very important for us here in Pakistan to address racism in our own society before we start railing at Europeans for being racist.

The first cry that goes up from the Muslim side when the issue of niqab or hijab is raised in Europe is that Europeans are racists, and that their criticism of certain aspects of Muslim “culture” amounts to a blatant swipe at a Muslim woman’s identity and religion. Yet when you actually look at the history of these pieces of cloth, it becomes clear that they originated as a symbol of class. Reference needs to be made to the fact that the veil was worn in pre-Islamic Arab society as a way of differentiating women of high social standing from slaves and prostitutes.

This brings me to one of the main problems which lead to violence and oppression in the Muslim world – racism. Yes, we Muslims are certainly not devoid of racism towards those we deem “lower” than us.

Growing up in Pakistan and being dark-skinned, I have experienced racism on the part of my peers. Even if they express it in a joking way, it’s there; it’s real. I’ve even been told by a close friend (a male who is Pathan in origin, hence very pale) that my features are beautiful – if only I were fair-skinned! I’m lucky enough to live in a subculture in which such things don’t matter. But the masses are constantly being fed with the idea that the lighter your skin colour, the more beautiful you are.

|

|

On any given day, one need only browse the Pakistani television channels for 30 minutes or so to get an idea of how deep-rooted this notion is. Because you’ll run across (for example) an advertisement showing you how a certain beauty crème entirely changed some girl’s life because it lightened her skin! In some cases the crème helped the girl to bag a husband; in other cases it snagged her the ideal job.

My own beautiful mother was told time and again by my father that she was lucky he married her, because she was dark-skinned. Racism, in short, is a stark reality of day-to-day life in Pakistan. It’s always there, in everything that goes on. If it isn’t about how light-skinned or dark-skinned you are, it’s about your actual racial origins.

Most honour killings of young couples are carried out because the victims married ‘out of the caste’. Syyeds (people who claim to be the direct descendants of the Prophet) are at the top of the hierarchy here. The bottom rung in Pakistan seems to be occupied by the Christians. They’re openly discriminated against, and are often referred to as “Chooras” – a disgusting term that is at once a slur against dark-skinned people and against Christians.

I remember clearly one time when a friend, who was also unlucky enough to be born brown in Pakistan, walked over to me at a party in tears. The reason? Her boyfriend had introduced her to his aunt, who was inebriated, and who said, “This is the girl you’re madly in love with? She looks like a Choori!” In one fell swoop the girl’s self-image was reduced to nothing. It didn’t matter that she was so beautiful that she could have been walking the ramp at international fashion shows, or that she had done brilliantly at school. No, what mattered was that she was dark, period.

Similarly, talking to an Arab of Jordanian origin once, I was blown away by the blatant racism in his interaction with anyone who was non-Arab. He proudly stated: “We’re brought up in an atmosphere in which we’re told that anyone who isn’t an Arab just isn’t as good as us.” The same individual had an American girlfriend for years. Then one day he came back from a visit to his country married to a young Arab girl. What was his explanation to our mutual friend, his girlfriend? “I always told you how I felt; I could never have children with a woman who isn’t an Arab!”

The problem is that racism prevails in our society. It’s ingrained. We feel that we’re better than anyone. It’s something we’re raised to believe. The racism doesn’t just pertain to skin colour. I’ve even heard mothers shout at their children for eating too fast with the admonition, “Stop eating like a bhooka [starving] Bengali!” Because we don’t even think that the Bengalis are as good as us, and clearly it’s okay to make your children feel the same way and to teach them that it’s a lowly thing to be poverty- stricken.

Someone once said that the prevailing problems in a society can easily be deciphered by analyzing the worst of the worst insults in its native languages. In Pakistan the worst insults are either misogynistic or racist, because nothing can be as bad as being “different”. This mentality coming from a nation of (mostly) converts! Yet most Pakistanis will proudly proclaim that they’re of divine decent – that they’re the children of the first Muslim armies that came to the subcontinent in A.D. 712. Of course, it’s not possible that that “pure” blood has been diluted since!

I’ve heard people in Pakistan – people with educated and wealthy backgrounds – refer to people of African origins as “Kalay”, meaning black in a derogatory way; to people of oriental origins as “Chaptay”, meaning flat-faced; and the list goes on. Sitting at the Norwegian embassy once, waiting for my turn to submit my visa papers, I heard one old man say to another, “I’m just going to visit my son. You can’t expect me to go and live forever in this suuar khanay walee qaum (pig-eating nation).” A young woman I know who recently returned from a holiday in Thailand said, “It was a nice place, but I just couldn’t stand it after a while – all Thai people have a particular stink!”

Take a look at the case of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman who is on death row in Pakistan for blasphemy. The whole argument began when she offered a few Muslim women a glass of water from which she had been drinking while they worked. The Muslim women refused to drink from the same glass, which angered Asia. What she said after that no one knows, since you cannot repeat blasphemy in Pakistani courts to prove or disprove it, but she was given the death sentence for it.

Hverdags-Rooshanie

Hverdags-Rooshanie